Alice Hamilton, the foremost practitioner of industrial toxicology in the early part of the 20th century, is widely considered to be a pioneer in industrial hygiene. Hamilton’s research on occupational illnesses in a variety of industries has influenced and inspired members of AIHA since the association’s founding in 1939. In a 2014

interview

with The Synergist

, historian Barbara Sicherman, who produced the biography Alice Hamilton: A Life in Letters

, shared her perspective on why Hamilton is still revered today. In addition to being one of the first Americans to study diseases in the workplace, Sicherman explained, “in the absence of formal institutions and regulations, [Hamilton] took it on herself to find individual and collective ways of preventing and controlling industrial diseases.” Sicherman also posited that “people find it intriguing that a woman … achieved so much in a line of work once considered very masculine.”

Much has changed since Hamilton’s time. Many more women have discovered a passion for preventing occupational illnesses. Hamilton’s is a familiar face for many in the industrial hygiene profession, and AIHA members may recognize some of the women who have filled top leadership roles in AIHA. For example, Anna M. Baetjer, best known for her work studying the relationship between chromium exposure and cancer, was elected the first female president of AIHA in 1951. ADVERTISEMENT

CLOSE

ADVERTISING

CLOSE

Who are the women working to ensure that today’s workplaces are healthy and safe?

The Synergist

spoke with several of them to illustrate the range of experiences and perspectives of female industrial hygienists.

OUTNUMBERED?

Like many professions, industrial hygiene was historically dominated by men, so it’s no surprise that female industrial hygienists still often find themselves alone or in the company of only a few female colleagues in a room full of men. After Baetjer served as the first female president of AIHA, 35 years passed before members elected a second female president, Alice C. Farrar, in 1986. Sixteen years later, Gayla J. McCluskey helmed the organization in 2002. The lack of female organizational leaders in AIHA’s early years and beyond mirrors what industrial hygienists who have been practicing for decades recall from their first years in the profession.

When current AIHA President Deborah Imel Nelson, PhD, CIH, first attended AIHA’s annual conference in New Orleans in 1977, she remembers being one of the youngest people as well as one of very few women. Stacey Croghan, CIH, who has been in the field for more than 20 years and recently opened her own consulting business, was one of only two female graduates when she completed her undergraduate degree in chemistry. Later, Croghan frequently found herself in meetings where she was the only woman. She has worked for only one female boss during her career, not including herself.

Location also affects the ratio of female to male industrial hygienists. Toral Mehta, CIH, CSP, who works for a pharmaceutical company in Austria as a subject matter expert in industrial hygiene and containment, became one of the first three female industrial hygienists in India in 1999, when the profession was still relatively new to the country. Mehta isn’t certain how many practicing female industrial hygienists there are in India today, but she is sure they still can be counted on two hands.

Today, Nelson sees an increasing number of women attending AIHce, Mehta expects to see more women stepping into leadership and managerial positions, and Croghan notices women taking on more responsibility in all professions, not just industrial hygiene. AIHA’s Board of Directors has more women at the table; more than half of the officers and directors on this year’s Board are women. Since McCluskey’s presidency in 2002, AIHA has been led by six other women, including Nelson. President-elect Cynthia A. Ostrowski, CIH, will take over later this month at AIHce EXP, and Kathleen S. Murphy, CIH, will succeed her the following year. For the first time, AIHA will have had three consecutive female presidents. ADVERTISEMENT

CLOSE

But this trend isn’t necessarily happening across all industries; female industrial hygienists in the military, for example, still don’t have many female colleagues. Maj. Crystal Brown, CIH, CSP, is a bioenvironmental engineer (BE) in the U.S. Air Force. As a flight commander, she oversees 24 individuals—two of whom are women—but she is the only female BE officer on the installation.

It’s not just the lack of female colleagues that some women in the field notice. Depending on the industry, workers may also be predominantly male. Ivory Iheanacho, MSPH-IH, a young professional who now works as a consultant for an international projects, engineering, and technical services company, has experienced this firsthand in the oil and gas industry, as has Mehta, who once spent several days working on an oil rig in the middle of an ocean.

Many industrial hygienists—both women and men—know what it’s like to be the only one on a work site. While it can be challenging for anyone to be the “lone IH,” women face issues that their male colleagues often don’t.

Air Force Maj. Crystal Brown works on an indoor air quality meter.

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES

The spread of the “Me Too” movement has increased public awareness of the prevalence of sexual assault and harassment, particularly in workplaces. Time’s Up, an organization founded earlier this year to address “the systemic inequality and injustice in the workplace,” also seeks to improve safety and equity for working women. In general, the women who spoke with The Synergist

don’t feel that they experience harassment, bullying, or related issues at an increased rate compared with women in other professions, but they do notice that they’re sometimes treated differently.

“We face problems similar to those of other women professionals, including workplace bullying and sexual harassment,” Mehta says. “The challenges are ongoing, and we have to deal with it in any work environment, including the industrial hygiene profession.”

Iheanacho explains that these issues can be more difficult for young professionals. They might not know whether something that happened to them is considered harassment, they might not have a trusted colleague with whom they can discuss these scenarios, or they may worry about even raising the subject. Iheanacho recalls that she had just started a new job and was working alone on a client site when a male employee of her client made an uninvited advance.

“It was a stressful moment, but I did the best I could do, which was to address the situation,” she says. “But it would have been nice to feel like I could talk to someone about it. I didn’t want to seem like I was complaining. I felt embarrassed to even bring it up.”

“That wasn’t a part of my training,” Iheanacho continues. “How do I advocate for myself without coming across as confrontational or aggressive, yet in a way that is direct?”

Other women who spoke with The Synergist

had similar stories. Nelson mentioned that she didn’t speak out about an incident because she felt like she might be labeled a “whiner” or a “complainer.”

Interviews with women in industrial hygiene suggest that there’s now a greater awareness among their male counterparts—and men in the workplace in general—to “remain professional.”

“Other people describe it as ‘being appropriate,’ but I would just say ‘remaining professional’—not saying things that could be misconstrued or commenting on someone’s appearance,” Iheanacho says.

Brown notices that people clean up their language around her when she goes out to industrial shops, which are typically dominated by male workers.

“If I was a male, they’d be a little more jocular,” she says. “With me, they’re very correct—sometimes even kind of rigid until they get to know me.”

The culture has come a long way during the 12 years Brown has served. She encounters far fewer rude jokes and sexist comments because it’s been made clear that it’s not okay.

Cultural changes can be measured in other ways. For example, years ago, female industrial hygienists had trouble finding properly fitting safety equipment. Nelson recalls that when she started at OSHA, there was only one option each for safety shoes and safety glasses. The only respirator that fit her was not NIOSH certified. The variety of safety equipment now available for women and for people of different sizes and shapes benefits both industrial hygienists and workers.

Croghan has also noticed a gradual culture change in her work as a consultant, but notes that issues related to equal pay remain for women in industrial hygiene. She recalls not negotiating for herself well enough when she entered the profession because she didn’t know what she was worth. Her company worked with her and gave her several raises, but it was a challenge for her to catch up with those who had similar or even less experience. Many employers now ask candidates to provide their salary history, which Croghan says can make it more difficult for women to “get out of the hole.” Many industrial hygienists—both women and men—know what it’s like to be the only one on a work site. While it can be challenging for anyone to be the “lone IH,” women face issues that their male colleagues often don’t.

But the women who spoke with

The Synergist

don’t see any of these issues as factors that restrict women from entering and succeeding in the profession. They are eager to share stories of what inspires them in their work. For example, Iheanacho will always remember the time an oil and gas worker thanked her for taking the time to conduct an earplug fit test that showed him the importance of inserting his earplugs properly. Mehta’s international consulting and corporate experience allowed her to work in a wide range of industries, many more than a layperson would see in a lifetime. Brown never gets bored in her job, and she enjoys benefiting people while she’s at it.

LEVERAGING OPPORTUNITIES

Interviews with practitioners suggest that many women in industrial hygiene feel that they must work a bit harder to prove themselves. Veterans of the profession remember feeling like they sometimes didn’t have a voice or that their experience was not recognized by their colleagues. Croghan says that changed for her after she gained about 10 years of experience. Becoming a Certified Industrial Hygienist also seemed to ramp up her credibility in the eyes of others. She notices that people take her more seriously now than when she was younger. Brown says that rank in the military has been a great equalizer; as she moves up, people take her more seriously as well. Other women shared similar feelings—that after years of experience, promotions, and certification, their voices and opinions carried more weight.

Some women, like Mehta, believe that the extra effort women have to put in to their work makes them stronger. Even though she’s in her 18th year in the profession, she, like many other women, still feels the pressure to continuously prove her knowledge, experience, and skills.

Aileen Yankowski, MPH, CIH, past chair of AIHA’s Career and Employment Services Committee and current leader of the newly formed Women in IH Working Group, encourages women to use this to their advantage.

“Take the project no one else wants and do something difficult,” she urges. “In those cases, you can shine because no one else can do it.”

Yankowski has had several good mentors—not all of whom were women—who taught her how to give better presentations, navigate workplace politics, and sell her ideas. When she coaches people on career-related issues, she often encourages women to be more confident.

“Some don’t know that you can ask questions like, ‘What will it take for me to get promoted?’ or ‘How do I get a better score on my performance review?’” she says.

SHARING LESSONS LEARNED

Most industrial hygienists agree that it’s impossible for one practitioner to know everything. Iheanacho and others interviewed for this article point to the strong sense of collaboration and camaraderie among their teammates and others in the profession.

“I can call former classmates, instructors, or colleagues and ask questions I think they might be able to help with,” Iheanacho says. “If they know it, then they’re happy to share, and if they don’t, they’ll generally reach out to someone else to find the answer.”

In this same spirit of collaboration, the women who spoke with The Synergist

were keen on sharing what they’ve learned with others in the profession—both women and men—and each has advice for women who are just beginning their careers.

“Know your audience,” Brown advises. “Every single person hears things differently. If you can talk to them in a way they understand, they’ll be more likely to do what you need them to do.”

“Look into getting a mentor—someone you can talk to,” Croghan says. “Mentors can guide you and give you advice on obtaining certifications or additional education to help further your career.”

“Whether you’re the younger person or you’re the only woman, advocate for yourself,” Iheanacho urges. “Express yourself and make your ideas known. You’re not going to be seen in a negative light for speaking up.”

“Gender is not a limiting factor for the industrial hygiene profession,” Mehta says. “Women have special qualities like compassion, empathy, and humility, and these are the assets we need to put to use in our profession.”

“Get actively involved in AIHA, especially if you’re in a workplace that doesn’t really encourage women,” Nelson says. “The association can provide experiences or opportunities that you won’t get at work.”

“If you’re out in the field a lot, especially in heavy industrial settings, you have to be strong,” Yankowski says. “You’ve got to make it work. You can change a person’s health and future; this is one of the few professions in which you can make a difference in someone’s life.”

KAY BECHTOLD

is senior editor of The Synergist

. She can be reached at (703) 846-0737 or via email

.

Disclaimer: Crystal Brown is a member of the Air Force. Use of her military rank, job title, and photographs in uniform does not imply endorsement by the Department of the Air Force or the Department of Defense.

Send feedback to The Synergist.AIHA’s Women in IH Community

The mission of the new Women in Industrial Hygiene Community is to “provide a platform for professional women to support career development, promote leadership skills, and to share information relevant to women working in industrial hygiene.” AIHA members leading the community encourage both women and men to get involved, attend community meetings, and volunteer to help develop business and leadership training tailored for women, to address some of the issues outlined in this article.

This month, the Women in IH Working Group will host an open forum and present two educational sessions at AIHce EXP 2018. Learn more about these events and how to get involved in the community by reading a recent SynergistNOW

blog post

from Stacey Croghan, one of the founding members of the Women in IH Working Group. Members of AIHA can also connect with the Women in IH Community on Catalyst, AIHA’s online community platform. Interested individuals should fill out the contact form

and request to join the group.

The Experiences of Women in Industrial Hygiene

In Hamilton's

Footsteps

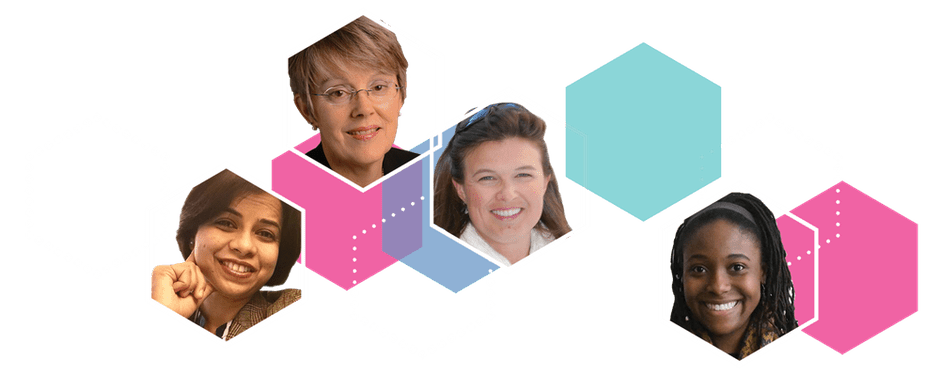

(L to R): Toral Mehta, Deborah Nelson, Stacey Croghan, Ivory Iheanacho, and Alice Hamilton.